“FleeceGPT” mobile apps target AI-curious to rake in cash

Credit to Author: Jagadeesh Chandraiah| Date: Wed, 17 May 2023 10:00:36 +0000

OpenAI’s ChatGPT, the large-language-model-powered artificial intelligence application, has dominated technology media coverage and permeated popular culture. Hoping to cash in on curiosity about ChatGPT, we’ve seen a spike in mobile apps claiming connection to the AI platform that fall into a category we refer to as “fleeceware,” apps that have behaviors similar to these:

- Their functionality is available for free through either the mobile OS itself or other sources online.

- They push the user toward enrolling in a short free trial that converts to a high recurring subscription charge to rake in money from unsuspecting users.

- They use intrusive advertising and other features to make the free version barely useable and to push the user toward the subscription.

Both Apple and Google have store guidelines intended to prevent app fraud, and these guidelines have evolved in response to earlier generations of fleeceware. When we first wrote about fleeceware back in 2020, some of these apps were charging more than $200 per month. New app store policies were intended to curb this; for example, developers have to be upfront about their subscription fees, and have to allow users to cancel free trials before incurring any charges.

Since then we have seen fleeceware evolve to circumvent those policies. In addition to repeated prompts to subscribe users, ranging from $9.99 to $69.99 on the apps, they also use tactics such as tightly limiting app usage and functionality without a subscription.

Because fleeceware applications are designed to stay on the edge of Apple and Google terms of service and do not access private information or attempt to circumvent platform security, they are rarely rejected during review and are allowed into the app stores. And these apps not only generate cash for the underhanded developers, but also enrich the platform owners through their cuts of app store sales—in the case of Apple, that’s 30% in the first year and 15% from the second year. As a result, there’s little financial incentive for Apple or Google to remove them despite their near-zero functionality and abuse of stores’ reviews systems to artificially boost their credibility.

Using a combination of advertising within and outside of the app stores and fake reviews that game the rating systems of the stores, the developers of these misleading apps are able to lure unsuspecting device users into downloading them, often with “free trial” versions that then kick in automatic recurring subscription fees that users may not know are coming, or prompt them to buy subscription to “pro” versions that promise greater functionality but fail to deliver.

The prime characteristics that make an app “fleeceware” are charging for functionality that is already free elsewhere, and the use of social engineering or coercive features to get users to sign up for a subscription to generate regular cash flow, as opposed to paying a one-time charge. While OpenAI offers an API for GPT and ChatGPT to developers at a rate that amounts to about $0.06 US for every 750 words of output, and has offered a $20-a-month “pro” subscription to the latest ChatGPT (which guarantees availability during peak usage and provides early access to new functionality), the basic functionality of ChatGPT is available freely to users through OpenAI’s website. All of the apps were offered as free (with little or no mention of subscriptions required to unlock basic functionality), had aggressive monetization tactics, and came with default subscription rates that were in many cases not in line with the functionality they provided.

We have reported the apps we found to Google and Apple. Some we were investigating were pulled from the store before we could report them. Google has responded and removed some of the apps we found, and Apple has acknowledged our input on the apps though no action has been taken at this time. We also reported ads for these apps on platforms where we found them.

Limited intelligence

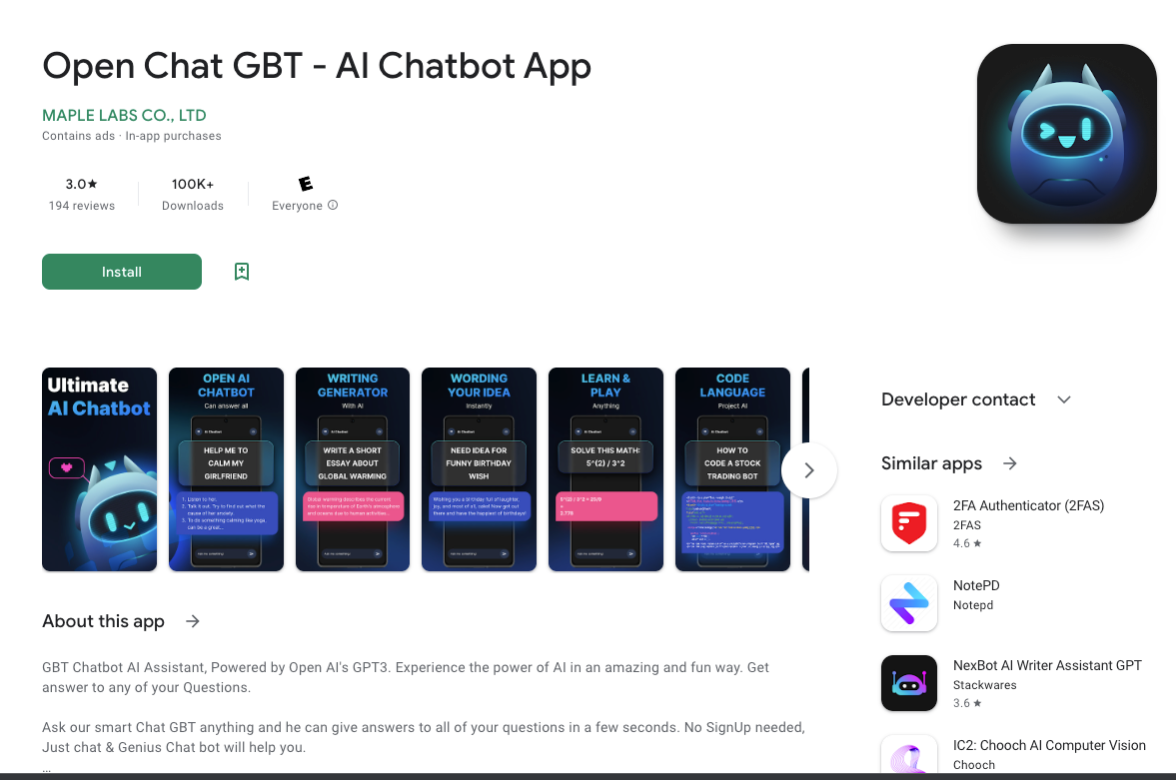

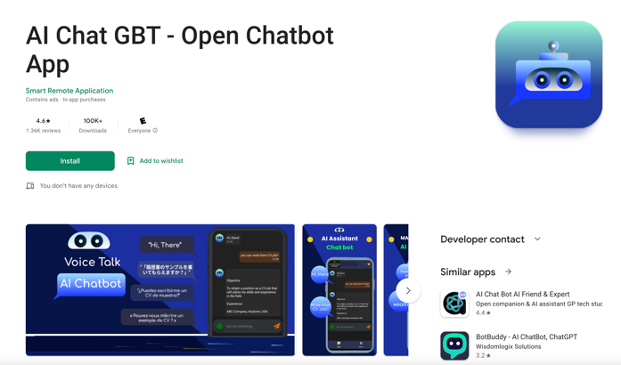

Our investigation into fleeceware chatbot apps (“FleeceGPT”) began when Sophos X-Ops principal researcher Andrew Brandt recently spotted an advertisement on a mobile news application for an Android application called “Chat GBT.” The Google Play Store listing included a logo that looked like the OpenAI logo for ChatGPT, and the developers call it “an alternative to chat GPT,” while also claiming, “We’ve trained a model called Chat GPT.”

But a quick download of the app revealed that it follows a pattern we’ve seen previously in other types of “fleeceware”. The “free” app was advertising-heavy, and locked after just three uses—prompting users to pay for a subscription to upgrade the software for further uses. The default option for the three-day trial is a monthly $10 subscription that kicks in automatically after the trial ends; alternatively, the user can pay $30 upfront for an annual subscription. If the user opts for for annual subscription they’ll keep paying that $30 every year until they unsubscribe—a much more profitable option for the fleeceware developer.

The ”pro” features that users pay for are essentially the same as available for free to registered users of ChatGPT—that is, if and when they work. Mixed in with the thousands of brief four-star reviews are comments from people who downloaded the app and found it didn’t work—either it only showed ads, or failed to respond to questions when unlocked. One user reported that the “reply to every message is ‘sorry, I could not understand your message.’”

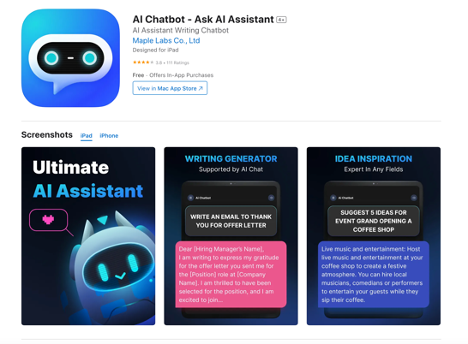

We found a nearly identical app with a different name from the same developer on the Apple App Store for iOS.

Called GAI Assistant, it behaved in the same fashion as the Android version we examined—users were limited to three inputs per day before being locked out and prompted to enroll in a free 3-day trial, which would automatically become a $6 US (or £6 for UK users) weekly subscription fee.

After a recent update, it behaved in a slightly different way, responding to all prompts with an abbreviated version of the reply and a “Read More” link at the end. It’s clear that it’s using OpenAI’s ChatGPT API, but it does not return any full, useful replies.

Tapping the “read more” link brings up a prompt for users to enroll for the three-day free trial or prepay for a monthly or annual subscription. And the interface now has a 10 query-per-day limit, again prompting the user to “go premium” when that limit is reached.

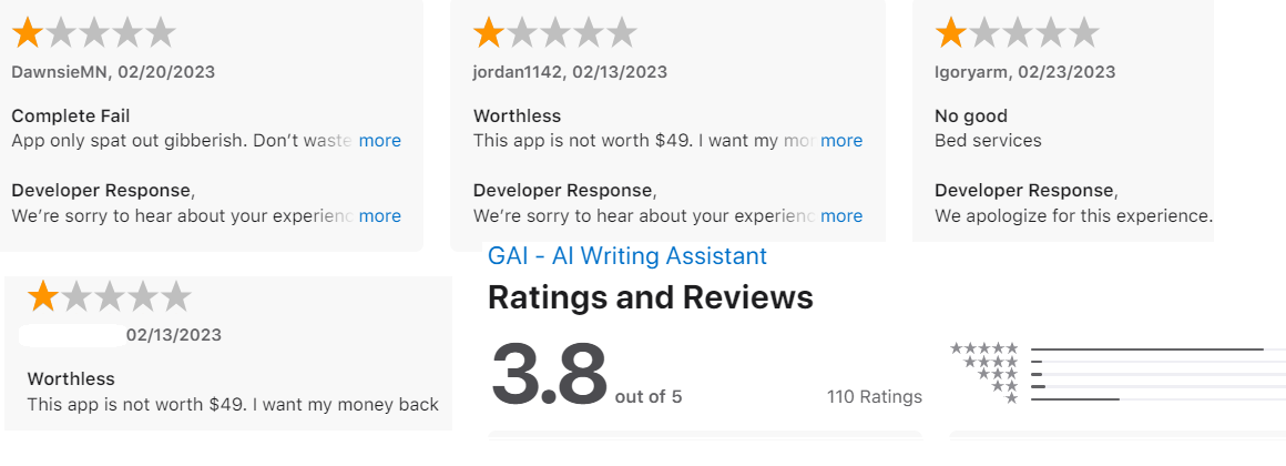

According to the app tracker Sensor Tower, the Android app had brought in under $5,000 in March , while the iOS version had yielded over $10,000 in revenue in March. That’s despite a pile of negative reviews that have begun to put a dent in the impact of dozens of fake 5-star reviews:

In one of the visible reviews on the site, a user wrote, “The entire app is just one big ad hub. There is virtually no app.” The developers responded that the ads were necessary to fund development, and added, “If you don’t want to see the Ads you can purchase the Pro version of ChatGPT. Please rate us 5★ to support the team! Thank you for understanding!”

Once a user assents to the 3-day trial, the app functioned mostly as advertised, and advertising disappeared. But aside from a bare-bones synthesized voice readback of responses, it’s not clear that the functionality exceeded what is available to users for free via mobile web browsers.

Copycats breed copycats

These developers aren’t the only ones trying to cash in on the buzz (and potential confusion) around ChatGPT. We found a number of other apps of a questionable nature on both the Play and Apple App stores—including ones that used almost exactly the same questionable naming to boost their results on store searches.

In the Google Play store, we found another app that uses an almost identical advertisement to the first fleeceware AI app we identified:

This “chatbot” has similar habits: the “free” version is limited to 4 requests before locking and prompting the user to purchase a subscription or sign up for a free trial that converts to a monthly subscription.

There were several other suspiciously-named apps in the Play store, but a few were pulled from the store during our research. And others, despite being buggy and carrying advertising, did not use typical fleeceware monetization methods.

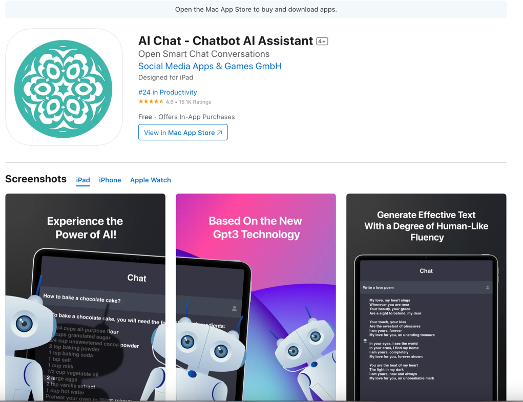

In the Apple App Store, we found several additional apps riding ChatGPT’s coattails that displayed fleeceware-like tactics. AIChatChatbot (or, as it identifies itself in the app window “Pocket AI Chat”) mimics the OpenAI logo in its store listing.

The interface itself is essentially a repackaged mobile site, and all content is generated remotely, including Google-served advertisements. There are several other behaviors that this app has in common with ones we’ve categorized as fleeceware in the past. First, there’s the types of permissions the app requests.

When installing, the app requests permissions to track user activity across other apps and websites. While it does connect to ChatGPT through a back-end server run by the developer, and provides the response to the input, it is also sending back telemetry the developer claims will be used “to collect Crash Data in order to improve functionalities.”

Like the other apps, it’s never really clear what the name of the app is. It is called “AI Chat – Chatbot AI Assistant” in the ad listing, and “Writing BOT Pocket AI” in the installation and user interface. Once installed, as with the others, the app also regularly interrupted application use with a window prompting for free trial signup—with automatic subscriptions at $8 a week—that could only be bypassed after waiting a few minutes for a window-closing “x” to appear. If not an outright violation of App Store policies (“Interstitial ads or ads that interrupt or block the user experience must clearly indicate that they are an ad, must not manipulate or trick users into tapping into them, and must provide easily accessible and visible close/skip buttons large enough for people to easily dismiss the ad”), this comes very close.

Replies were also often interrupted by requests to rate the app—another practice that stretches the envelope of Apple policy (“Apps must not force users to rate the app, review the app, download other apps, or other similar actions in order to access functionality, content, or use of the app”).

While there is no message limit if you’re willing to wait out the advertisements, there is a character limit for responses—likely driven by the version of the OpenAI API used by the back-end server. Responses appeared to be truncated at about 1000 characters to keep the number of GPT “tokens” used per request to a minimum.

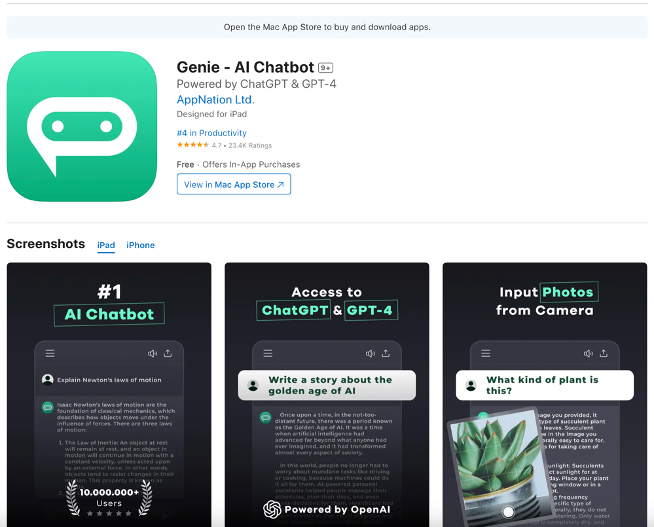

Another ChatGPT offering on the Apple App Store with some fleeceware-like behaviors is the “Genie AI Chatbot.” The app’s listing advertises it as the “#1 AI Chatbot” and touts features including image recognition as well as the usual text generation capabilities associated with ChatGPT.

There are a few fleeceware-like things about Genie, however. First, during installation, there are prompts to allow the app to track activities across other apps and websites, and to rate the app before it’s even fully launched. Genie also asks for permission to send notifications. These prompts are followed by one encouraging enrollment in a free trial or immediate enrollment in a longer subscription–$7 a week (totaling $364 a year), or an all-at-once $70 a year.

Unlike some of the others, Genie actually works at something approaching full advertised functionality without the trial or subscription—but only accepts 4 queries per day. It then prompts users with the trial offer again.

Figure 16. It works, until it doesn’t.

This model appears to have been effective for Genie’s developers. According to Sensor Tower, the app has generated over $700,000 in revenue in just the last month.

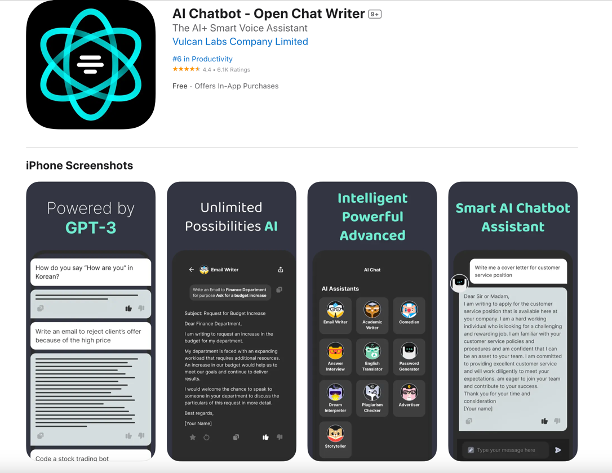

The third fleeceware-ish app we identified on the Apple App store was listed as “AI Chatbot-Open Chat Writer”, but when installed called itself “AI Smith”.

The screen shots on the listing site look nothing like the app that actually installs.

“AI Smith” has a five-message limit per day without a subscription, and those messages are interrupted by advertising and subscription screens, and constant requests for a rating.

As with some of the other apps we looked at, AI Smith does use a GPT-3 API to generate the content, but truncates content if it is too long.

We found many other apps jumping on the ChatGPT band wagon following a similar naming convention in an effort to attract users searching for the right app. But not all used fleeceware tactics. Many are just poorly written or poorly implemented apps that don’t fit the usual fleeceware formula.

Caveat Downloader

While we were investigating several other potential fleeceware apps, they were removed from the Google Play store. Google has since removed the apps we pointed out to them as well; similar apps, however, have been allowed to remain in the store.

Fleeceware developers have adapted to these guidelines and follow them to the letter—but not the spirit. They attempt to get customers to pay subscription fees in several ways, but mostly count on users forgetting about the free trial and not noticing the weekly or monthly subscription fees when they kick in, or they simply expect to yield enough from the initial subscription to profit.

The platform owners profit heavily from these applications as well, and there’s little incentive for them to remove applications that are not in obvious violation of standards. Because of this, mobile device users need to continue to pay close attention to in-app payments and subscriptions tied to “free trial” software. On Apple devices, those subscriptions appear in the settings menu under your Apple ID; on Android devices, Google Play subscriptions are managed within the Google Play store app under Subscriptions on the pop-out menu.

We recommend that Apple ensure that App store reviews include a close look at whether in-app subscriptions under the “freemium” model actually provide value rather than leaving it up to the device user, since these app stores present themselves as trusted platforms while profiting significantly from misleading apps themselves.

Additionally, because some of these apps are essentially re-wrapped web apps dependent on a remote platform for content, they pose a long-term risk in that their functionality could be made malicious by the developer without changing any local code. This is a tactic we have seen used by sha zhu pan scammers.

For now, the only real defense is user education. Before tapping the install button, users need to make sure they’re aware of any in-app purchases associated with a free app, and evaluate whether the fees associated with any application are in line with what’s available elsewhere. And when applications use unethical means to profit, users should report them to Apple or Google.

How to cancel a subscription

If you’ve discovered you have installed a fleeceware app, it’s important to note that just deleting the app will not end the subscription. Some victims of fleeceware install a trial and delete the app after trying it—not realizing that the subscription still remains on their app store account, and that their account will continue to be debited after the trial expires. Here’s how to remove these subscriptions:

IPhone

As outlined by Apple here by Apple, follow the instructions below:

- Open the Settings app.

- Tap your name.

- Tap Subscriptions.

- Tap the subscription.

- Tap Cancel Subscription. You might need to scroll down to find the Cancel Subscription button. If there is no Cancel button or you see an expiration message in red text, the subscription is already canceled.

If you have other use cases, please follow the Apple documentation.

Android

1.On your Android device, go to your subscriptions in Google Play.

2.Select the subscription you want to cancel.

3.Tap Cancel subscription.

4.Follow the instructions.

IOCs are available on our GitHub repository.