Fraudulent “CryptoRom” trading apps sneak into Apple and Google app stores

Credit to Author: Jagadeesh Chandraiah| Date: Wed, 01 Feb 2023 11:00:48 +0000

CryptoRom is a romance-centered approach to financial fraud and a form of what is also known as “pig butchering” or “sha zhu pan” (杀猪盘, literally “pig butchering plate”). This type of fraud uses social engineering in combination with counterfeit financial applications and websites to ensnare victims and steal their money. For the past two years, we’ve researched such scams, and have examined ways that their operators have evaded Apple’s security checks by avoiding the app store and using ad-hoc methods to drop malicious applications onto victims’ phones. Recently, we discovered CryptoRom apps that defeated Apple’s and Google’s app-store security review processes, making their way into the official stores. Victims of the scam alerted us to the applications and shared details of the criminal operations behind them. In the process of researching the applications, we found other apps and uncovered information about the organizations behind these scam operations.

In both cases, victims were approached through dating applications (Facebook and Tinder). They were then asked to move their conversation to WhatsApp, where they were eventually lured into downloading the apps discussed in this report. While the highly developed profiles and backstories used to lure the victims into trusting the guidance provided by the criminals set the table for these scams, the ability to publish the apps used in these schemes in the official stores significantly contributed to their perceived credibility in the eyes of victims.

Both Apple and Google have been notified about these apps. Apple’s security team promptly removed them from that app store. Google recently removed the app we reported from the Play store as well.

Luring victims through dating apps

In the first case we investigated, the victim was based in Switzerland. The target met his “potential partner,” a person or persons who used a profile of a woman purportedly based in London, through Facebook Dating. As seen in the other cases, the scammer’s Facebook profile was replete with photos seeming to show a lavish lifestyle, including photos of high-end restaurants, expensive shops and destinations, and near-perfect and professional-looking selfies. It is very likely that the profile contents were purchased from a third-party vendor or were stolen from the internet.

Figure 1: The daily “life” of a nonexistent woman; some images were probably created by the scammers or by a paid provider, while others were likely stolen from elsewhere on the internet

To maintain the appearance of being from London, the criminals behind the profile posted events from BBC News, such as Queen Elizabeth II’s funeral, on the persona’s Facebook timeline. The persona also “liked” and followed organizations that indicated interest in the BBC and well-known Western companies.

Figure 2: Check-ins and likes in the persona’s profile helped the scammers build credibility for their creation

After establishing a rapport, the criminals behind the profile told the victim that “her” uncle worked for a financial analysis firm, and invited the victim to do cryptocurrency trading together. At this point the scammers sent the victim a link to the fake application in the Apple app store. They instructed the victim in how to start “investing” with the application, telling them to transfer money to the Binance crypto exchange and then from Binance to the fake application.

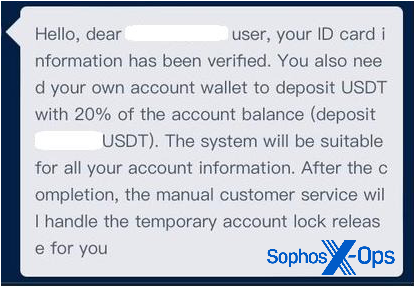

Initially, the victim was able to withdraw small amounts of cryptocurrency. But later, when the victim wanted to withdraw larger amounts, the account got locked and was told through a “customer support” chat in the application to pay a 20% fee (as shown in Figure 3) to access the cryptocurrency.

Figure 3: Once trust in the fake application has been established, the victim’s ability to withdraw money is suddenly “locked”

The second victim followed a similar path, with the difference that initial contact was through Tinder. The scammer asked to move the conversation to WhatsApp, and then prompted the victim to download a different fake app from the iOS App Store. The victim caught onto the scam, but only after losing $4,000 USD.

Fake Apps in Apple App Store

Previously, iOS apps we’ve seen associated with CryptoRom / pig butchering scams were deployed from outside the official Apple App Store via ad hoc distribution services. In order to get victims to install them, the criminals behind the scams had to use social engineering— they had to convince the victims to install a configuration profile to enable app installation, a process that could potentially spook many targets. But in cases we’ve investigated recently, applications used by the scammers were successfully placed into the Apple App Store, greatly reducing the amount of social engineering required to get the application onto victims’ devices.

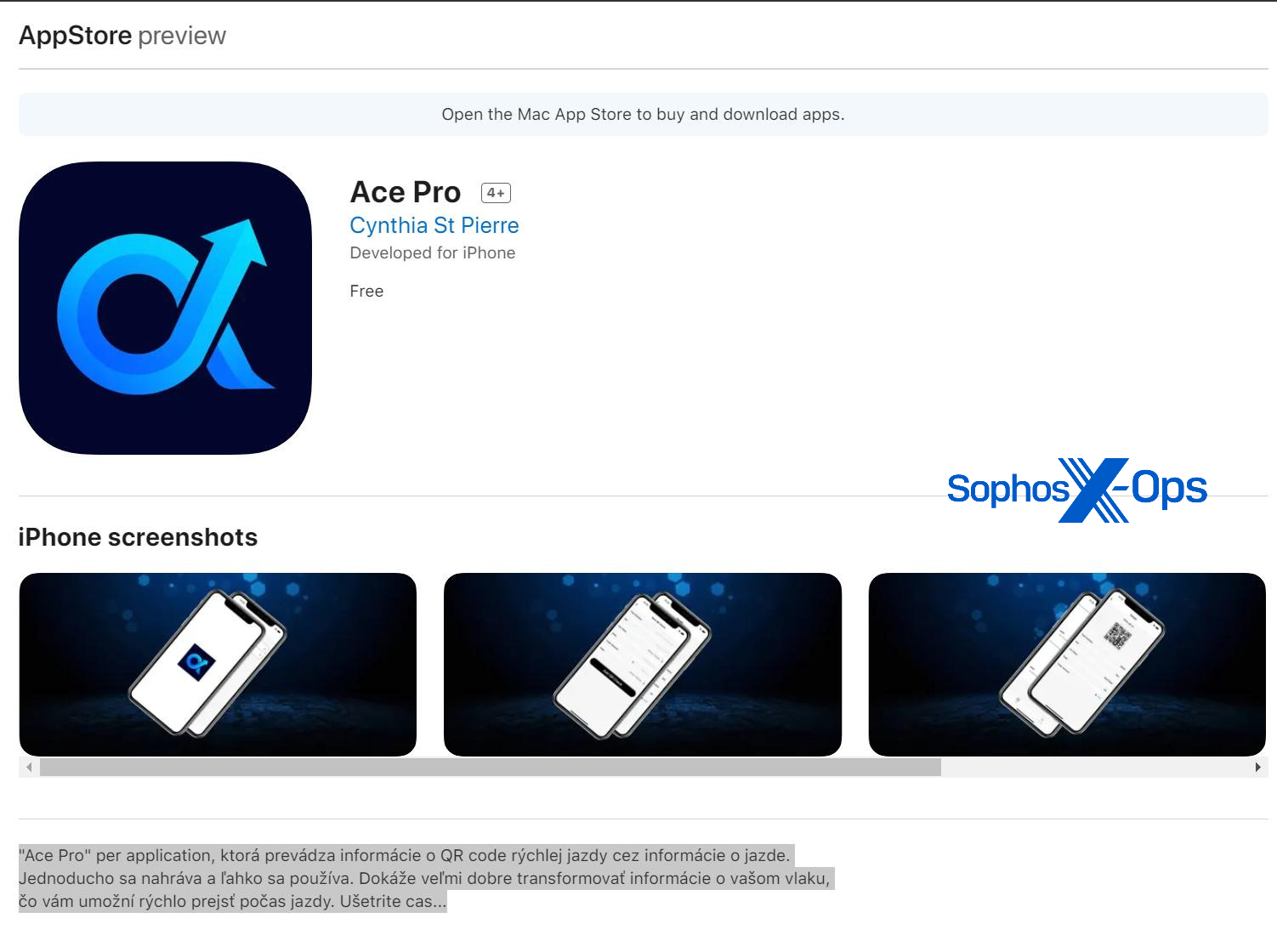

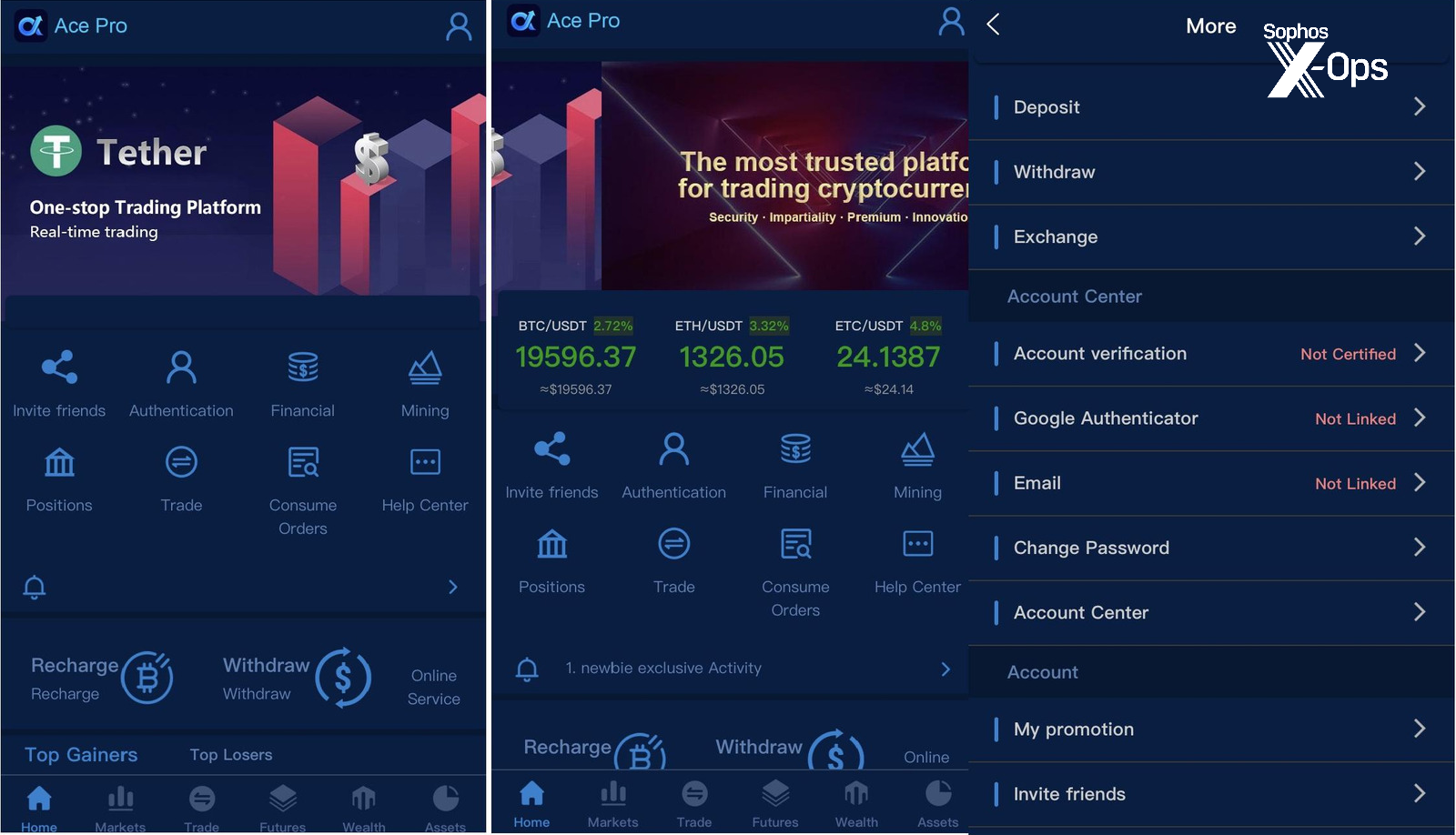

The first of these applications appeared on first inspection to have no connection to cryptocurrency; called “Ace Pro,” the app was described in its app-store page as a QR code-checking application.

Figure 4: The app-store download page for Ace Pro, since removed

The machine translation of the text (from Slovak):

"Ace Pro" per application, which converts QR code information of fast driving through driving information. It's simple to upload and easy to use. It can transform your train information very well, allowing you to quickly pass through the ride. Save time..."

The privacy policy for the application also describes it as a “QR Check” application.

Figure 5: The Ace Pro privacy policy

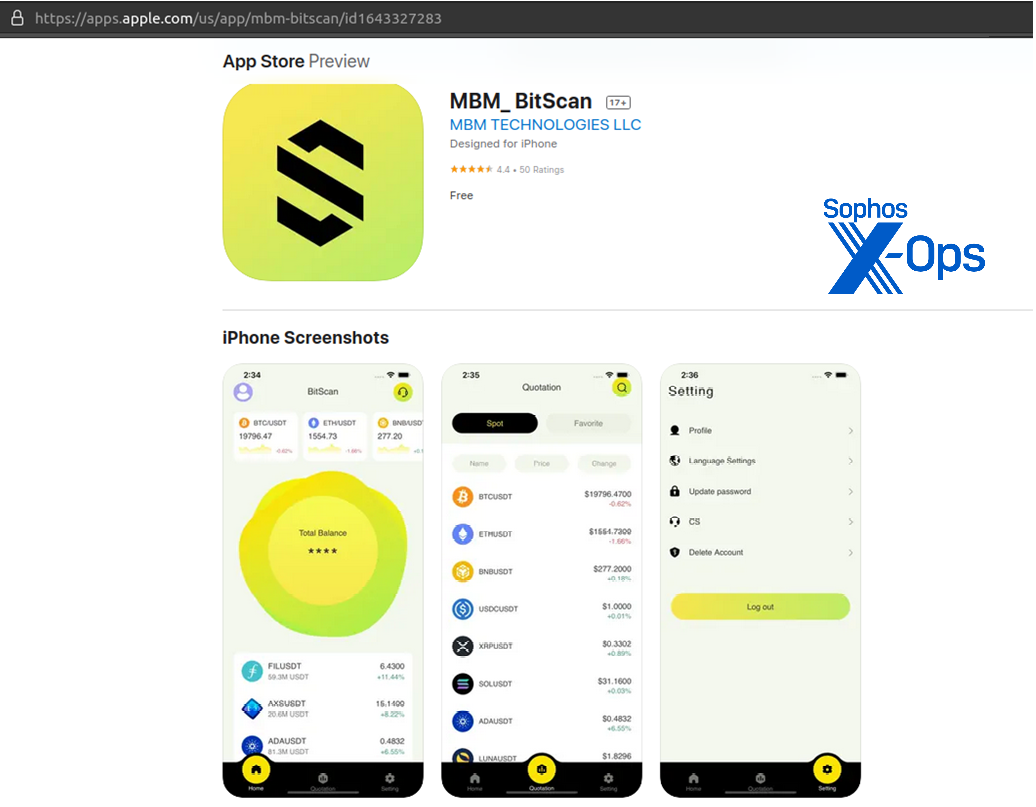

The second CryptoRom application we discovered in Apple’s app store was called “MBM_BitScan,” described in the store listing as a real-time data tracker for cryptocurrencies. But it also has a fake cryptotrading interface. One victim lost around $4000 to this fake application.

Figure 6: The app-store download page for MBM_BitScan, since removed

Both of these applications managed to get past the Apple App Store review process. All applications that are installed via the Apple App Store must be signed by the developer using a certificate provided by Apple, and must go through a stringent review process to verify that they follow the App Store guidelines.

If criminals can get past these checks, they have the potential to reach millions of devices. This is what makes it more dangerous for CryptoRom victims, as most of those targets are more likely to trust the source if it comes from the official Apple App Store.

Evading App Store Review

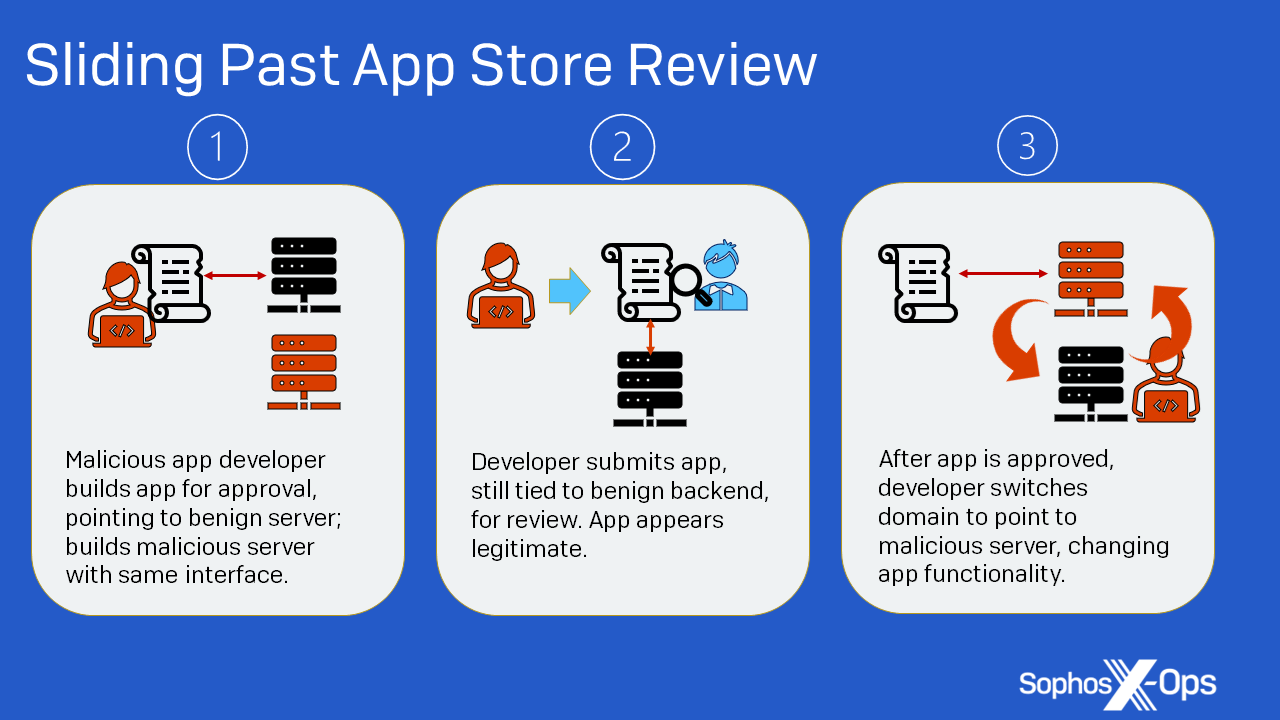

Figure 7: How fraudulent applications likely evaded the Apple review process.

Both the apps we found used remote content to provide their malicious functionality—content that was likely concealed until after App Store review was complete.

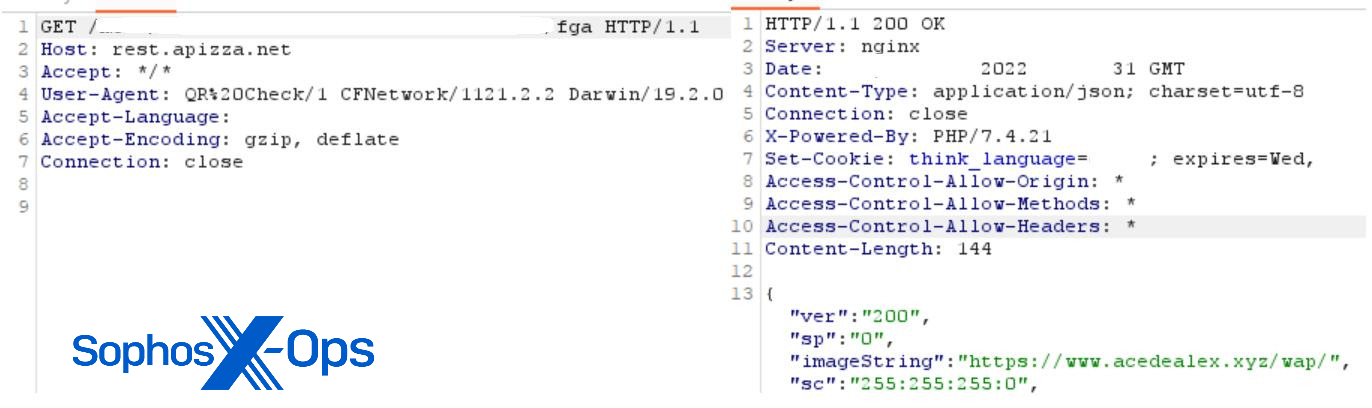

In the case of the Ace Pro app, the malicious developers inserted code related to QR checking and other iOS app library code in the app to make it appear legitimate to reviewers. But when the app is launched, it sends a request to an Asian-registered domain (rest[.]apizza[.]net), which responds with content from another host (acedealex[.]xyz/wap). It is this response that delivers the fake CryptoRom trading interface. It is likely that the criminals used a legitimate-looking site for responses at the time of the app review, switching to the CryptoRom URL later.

Figure 8: The captured web request and response from the Ace Pro app

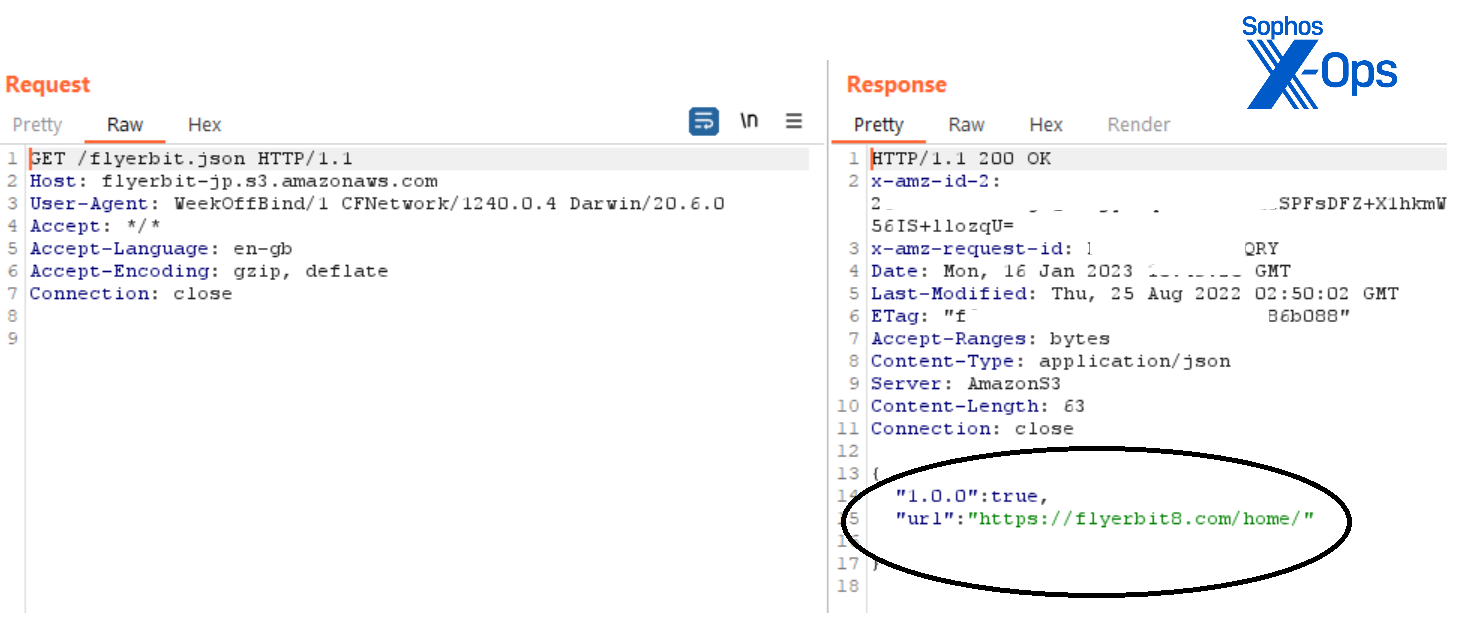

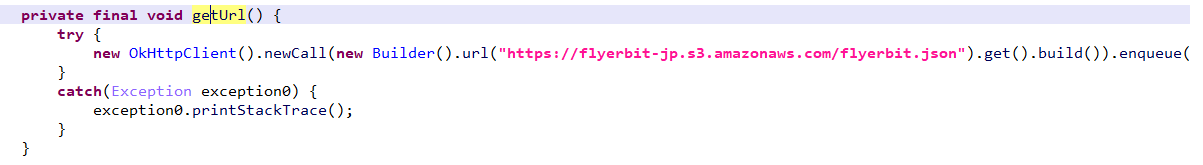

The MBM_BitScan app uses a similar approach. On execution, it sends a JSON request to a command-and-control (C2) server hosted on Amazon Web Services, and gets a response from a domain called flyerbit8(.)com —a domain crafted to look like that of legitimate Japanese bitcoin vendor bitFlyer:

Figure 9: The web request made by the MBM_BitScan app, and the response delivering the JSON package containing the URL of the malicious website serving up the fake trading app

This review evasion technique, which is connected to click-fraud malware, has been seen previously by other researchers in fake iOS applications dating back to 2019 .

Fake Crypto Interfaces

The remote content displayed within these applications is similar to other CryptoRom and pig butchering scam applications we’ve seen. Both have a working-but-fake trading interface with the purported ability to deposit and withdraw currency, as well as a built-in customer service function. But all the deposits go into the crooks’ pockets rather than an actual trading account.

Figure 10: The trading interface in the Ace Pro app

Figure 11: The MBM_BitScan fake-application interface, with an option to buy crypto

Because these trading interfaces are loaded at runtime, and because the entirety of the malicious content of the applications resides on the web server and not in application code, it is challenging for app stores to review and find these fake applications. They’re difficult to identify as fraudulent by reviewers by just viewing the code. And since they will likely only be used by people targeted by the scams, they will only get reported by targeted users who are familiar with legitimate versions of the applications and have an understanding of cryptocurrency. Because of these factors, these types of fake applications will continue to pose a significant challenge to Apple’s app security reviewers.

Google Play Store application

The Google Play Store version of MBM_BitScan has a different vendor name and different title than that of the Apple version. However, it communicates with the same C2 as the iOS version of the app, and likewise accesses the domain that hosts the fake trading interface via JSON. It receives flyerbit8<dot>com, which as noted above resembles the legitimate Japanese crypto firm bitFlyer. Everything else is handled in the web interface.

Figure 12: The MBM_BitScan app as seen on Google Play Store

Figure 13: The Android version of the MBM_BitScan app’s getUrl method, with an AWS-based URL that fetches the JSON data containing the CryptoRom interface

The actors behind CryptoRom rings

CryptoRom and other forms of “pig butchering” initially targeted people in China and Taiwan. Early scams focused on online gambling with insider information, using similar tactics to CryptoRom. Over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, the scams expanded globally and evolved into fraudulent foreign exchange and cryptocurrency trading. We are tracking this threat actor as the “ShaZhuPan” group.

When Chinese authorities started cracking down on these scams and prosecuted some perpetrators, some of the gangs behind them fled to smaller southeast Asian countries, including Cambodia, where they now operate in special economic zones (SEZ).

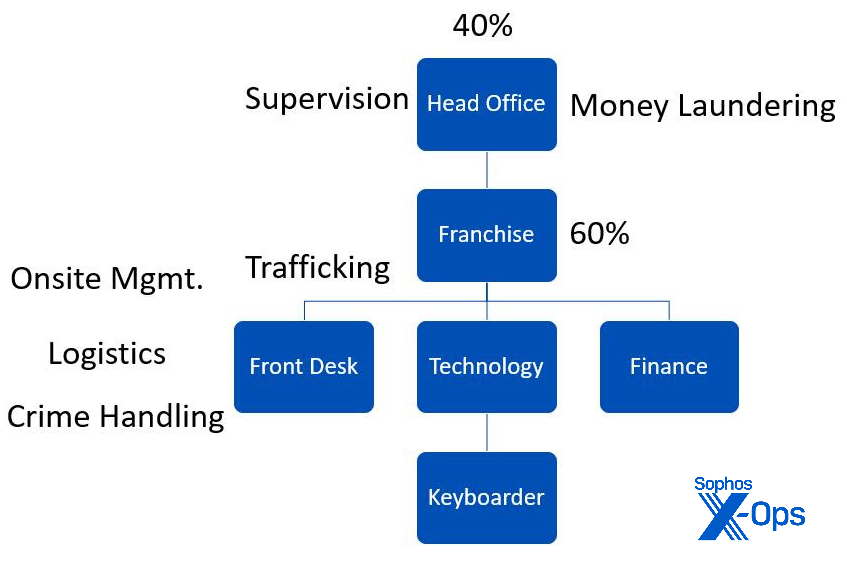

According to reports by Chinese law enforcement organizations who targeted these operations in China, CryptoRom groups follow a business structure that mimics a corporate organizational model. At the top is a head office, which does supervision and money laundering. The head office sub-contracts scam operations to affiliate organizations. These franchise operations, also called agents, have their own division of labor:

- The “front desk” team handles logistics, human trafficking (more on this below) of new workers, and site management.

- The tech team handles websites and applications.

- The finance team handles the local finance operations; profits are divided 40:60 between the head office and franchise.

- Keyboarders are at the bottom of the crime chain and are the ones that do the majority of interaction with the victims.

Figure 14: The org chart of a typical pig-butchering group

During Covid-19, many underdeveloped countries did not have jobs or sufficient social benefits to support those affected by economic disruptions. This pushed many young people into taking job offers in other countries’ special economic zones that promised high pay. Many of these were fraudulent job offers tied to pig-butchering rings; when workers arrived, they were transported to CryptoRom centers and had their passports confiscated.

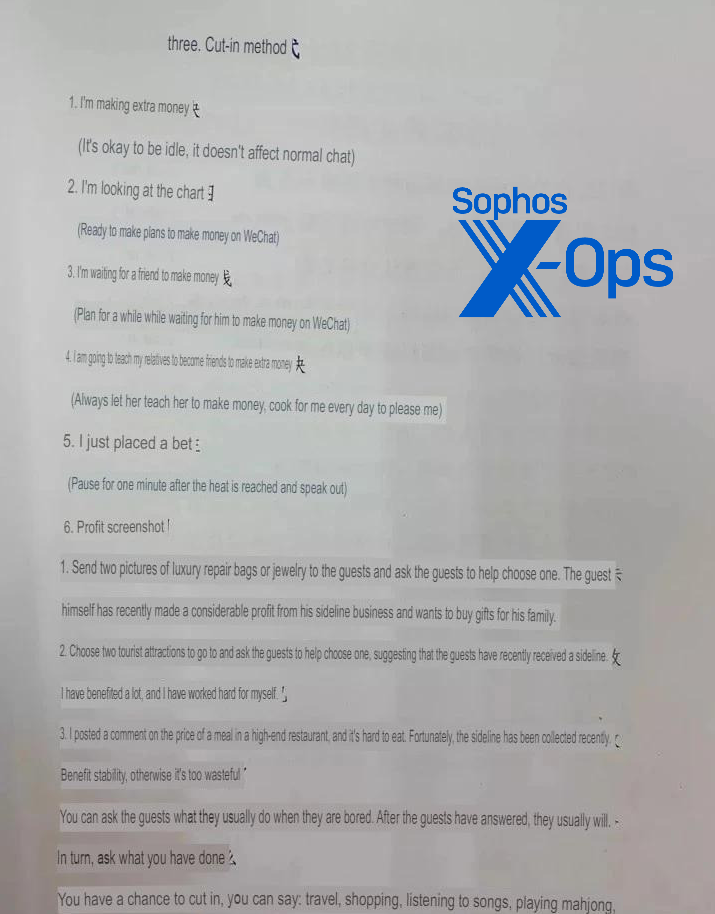

Often, keyboarders are these trafficked victims, brought from countries like China, Malaysia and India with the promise of better-paid jobs. They are trained with pre-written scripts with instructions on how to interact, what to say to their victims, and how to bring them into investing. If they want to leave or do not follow the script, they are reportedly subjected to violence.

Figure 15: Translated training manual posted on Reddit by a former keyboarder

Why do victims fall for this?

One of the questions that comes to everyone’s mind when reading these articles about people losing money to CryptoRom is, “Why do they do this?” Why do victims put so much money into these scams in spite of the many red flags along the way — especially when they have not even met the person face to face?

It’s easy to quickly judge them, but it’s wrong to dismiss the victims of these scams without understanding the circumstances that led them to fall for the schemes. After discussions with a number of victims and reviewing public postings by others, we identified some of the potential reasons they overlooked the threats. Many of the victims (both men and women) were well-educated; some even had PhDs. They were swayed by the persuasion techniques used in these scams:

- The length of engagement — the scammers can spend several months gaining the trust of the victim, chatting with them, greeting them, and sending images of typical day-to-day life. The victims may be less likely to research elements of the scam because of the persistence of the contact with the scammers.

- The proof of an initial withdrawal — the victims were convinced by the fact that they were allowed by the scam to withdraw money from initial transactions. This tactic is a well-worn method also used by traditional Ponzi schemes to make the confidence scam seem more authentic.

- Mirroring of transactions – The scammers use screen shots of the fake app to show that they are doing the same thing that they are asking the victim to do, and show the (fake) profits that they are making. They ask the victim to do the same transactions, while convincing them to increase their deposit into the fake marketplace.

- Fake lending – When victims have to pay fake tax, as a final blow, they pretend to pay half the tax bill for the victim and ask the victim to bring the other half.

There are other contributing factors making the victims potentially more open to persuasion:

- Emotional vulnerability — Most of them were vulnerable to emotional manipulation. In many cases, the victims were men or women who had experienced some sort of major life change. Some had been unsuccessful in the dating pool, were recently widowed, or had experienced a major illness.

- The rise of app-based finance – The emergence of “FinTech” (finance technology) companies without physical branches over the past few years has made it more difficult to spot the fake ones– especially when they’re presented by someone trusted.

- Platform trust – Finally, and perhaps most importantly, victims trust Apple and Google, which claim to verify and check all the applications distributed by their app stores.

Removing a CryptoRom App

If you installed a CryptoRom app through any app store, please just delete the application. On Apple devices:

- Touch and hold the app until it jiggles.

- Then tap the delete button (the X) in the upper-left corner of the app to delete it. If you see a message that says, “Deleting this app will also delete its data,” tap Delete.

If you installed the profile from outside the app store using a profile, these steps are recommended by Apple’s documentation:

- If the app has a configuration profile, delete it if you installed it

- Go to Settings > General > Profiles or Profiles & Device Management,* then tap the app’s configuration profile.

- Then tap Delete Profile. If asked, enter your device passcode, then tap Delete.

- Restart your iPhone.

* If you don’t see this option in Settings, then no device management profiles are installed on your device.

For Android users, from your phone you can delete the app from within the Google Play Store, or do the following:

- Long-press the app icon until the Select / Add to Home / Uninstall popup appears. Tap “Uninstall” (on the right).

- When the popup asked “Do you want to uninstall this app?,” choose “OK.”

- Confirm that the app is gone by going to “Settings” (the gear in the upper right corner of your screen), clicking on “Apps,” and scrolling to confirm that the app has not lingered.

Are you a victim and want us to check your app or URL?

If you have experienced this type of fraud or wish to report suspicious applications or URLs connected to CryptoRom or other malware at no cost, please reach out directly via Twitter to @jag_chandra.

SophosLabs would like to acknowledge Xinran Wu and Szabolcs Lévai for their contribution to this article.

IOCs

App URL – https://apps.apple.com/US/app/id1642848412

ID – com.QRCheck.APP

IPA – c336394b1600fc713ce65017ebf69d59e352c8d9how